Here is the relevant part of AN 5.100:

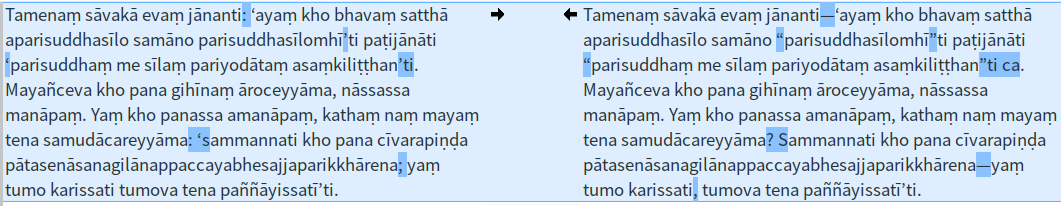

idha, moggallāna, ekacco satthā aparisuddhasīlo samāno ‘parisuddhasīlomhī’ti paṭijānāti ‘parisuddhaṃ me sīlaṃ pariyodātaṃ asaṃkiliṭṭhan’ti. tamenaṃ sāvakā evaṃ jānanti: ‘ayaṃ kho bhavaṃ satthā aparisuddhasīlo samāno parisuddhasīlomhī’ti paṭijānāti ‘parisuddhaṃ me sīlaṃ pariyodātaṃ asaṃkiliṭṭhan’ti. mayañceva kho pana gihīnaṃ āroceyyāma, nāssassa manāpaṃ. yaṃ kho panassa amanāpaṃ, kathaṃ naṃ mayaṃ tena samudācareyyāma: ‘sammannati kho pana cīvara-piṇḍapāta-senāsana-gilāna-paccaya-bhesajja-parikkhārena; yaṃ tumo karissati tumova tena paññāyissatī’ti.

Here is Ven. Bodhi’s take:

“Here, some teacher whose behavior is unpurified claims: ‘I am one whose behavior is purified. My behavior is purified, cleansed, undefiled.’ His disciples know him thus: ‘This honorable teacher, though of unpurified behavior, claims: “I am one whose behavior is purified. My behavior is purified, cleansed, undefiled.” Now he would not like it if we were to report this to the laypeople. How can we treat him in a way that he would not like? Further, he is honored with robes, almsfood, lodgings, and medicines and provisions for the sick. A person will be known by what he himself does.’

The commentary explains sammannati as sammanam karoti, which ven. Bodhi interprets as “do honor to” and then translates “he is honored”. But is there a grammatical justification why we should translate sammanati in the passive voice?

As for interpretation, I guess it means the disciples who depend on donations made to their master do not want to tarnish his reputation because it would also affect them if he starts receiving less.

I have looked up other usages of the term, and it seems to come up either as meaning “to appoint”, “to agree upon”, “to consent”, “to authorize” to perform a particular task. Here are two examples from the suttas, which seem to reflect most uses found in the Vinaya:

AN 5.272

“pañcahi, bhikkhave, dhammehi samannāgato bhattuddesako sammannitabbo.

Bhikkhus, one possessing five qualities may be appointed an assigner of meals.

AN 8.52

“katihi nu kho, bhante, dhammehi samannāgato bhikkhu bhikkhunovādako sammannitabbo””ti?

“Bhante, how many qualities should a bhikkhu possess to be agreed upon as an exhorter of bhikkhunīs?

From the Vinaya:

Nissaggiya Pc 18

saṅgho itthannāmaṃ bhikkhuṃ rūpiyachaḍḍakaṃ sammannati.

The Order agrees upon the monk so and so as silver-remover.

Sg 8

“tena hi, bhikkhave, saṅgho dabbaṃ mallaputtaṃ senāsanapaññāpakañca bhattuddesakañca sammannatu. evañca pana, bhikkhave, sammannitabbo: etc.

“Monks, let the Order consent that Dabba, the Mallian, should assign the lodgings, and should distribute the meals. Monks, this should be authorised thus: etc.

I first thought it might mean something like “assign” but that would be “paññāpeti”. However it seems to me that it could have a related meaning such as he “agrees to” or “authorizes” the use of robes, almsfood etc.

Understood in this way, it would mean that the disciples shut up about their master because they depend on his authority to get from him robes, almsfood etc.

The translation would then be:

Now he would not like it if we were to report this to the laypeople. How could we treat him in a way that he would not like when he gives authorization with regards to robes, almsfood, lodgings, and medicines and provisions for the sick

The only thing is that an accusative would make better sense than an instrumentative in the compound cīvara-piṇḍapāta-etc. But then again can the passive voice on sammanati in the alternative interpretation be grammatically justified?

Is there an element that I am missing that shows a clear reason to choose one interpretation over the other?