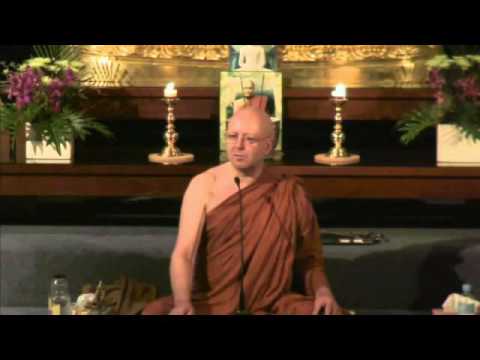

Ajahn Brahm makes it clear in his Jhana teachings. The abeyance of the ‘doer’ is a key-insight that arises as a consequence of samma-samadhi. This is an unmistakable happening - that comes and goes.

The sense of self, the basis of the delusion of the ‘doer’, comes and goes. When reaction-free attention is sustained, its unbroken, there comes a point where this delusional ‘presence’ may drop out of awareness.

This gives rise to a radical-shift in awareness during periods of stillness and, in daily life.

This ‘absence’ is a clear indication that something very-different is available here-and-now. What would it be like to lose our imaginary-friend, permanently?

A jhani understands the meaning of the following poem - directly:

“Sitting quietly, ‘doing nothing’, Spring comes, and the grass grows, by itself.” - Basho

The Dhamma is clear and undisguised!

If we simply live our daily lives with awareness in a kind way everything will be revealed in its own time and place.

Its never really doing something, its a process of not getting in the way. When we try to hold our attention on something the mind never really settles down.

When there’s genuine interest and a natural curiosity investigation takes place all by itself. There’s no need to direct the mind to focus on something if your heart is in it.

Natural stillness is not a process of doing something because the ‘doing’ makes the mind unstable.

We don’t need to try and hold the mind still. It’s nature is to move like a stream or river. We can simply let it go, let it be.

The holding, the attachment, fuels the movement of the mind.

‘Doing’ is a continuity of movement in the mind.

What else could it be?

Bare awareness is a shift from identification with doing to mere presence, close attention to what is happening without clinging or, identification with that which comes and goes.

The quality of attention feeds the momentum or, allows the mind to move towards stillness - towards cessation. Nibbana is the stilling of all formations.

“The escape from that is calm, permanent, beyond inference, unborn, unproduced, the sorrowless, stainless state, the cessation of stressful qualities, the stilling of fabrications, bliss”* - 43 Itivuttaka

In order to pacify a child we give them care-ful loving attention. The same with the mind - this  /mind - the same with everything.

/mind - the same with everything.

What are the natural stages of letting go**?

**T_The-Basic.pdf (132.9 KB)