You are right. I should have said Buddhists and Hindus or those who believe in rebirth due to religious conditioning.

With Metta

It is of vital importance to understand bhava as an experience rather than merely conceptually. For this is the most fundamental governing force in all living beings, including the simplest organisms which are incapable of thinking about anything at all, let alone developing a cognitive desire for rebirth. Bhava being the natural capacity (anuyasa) of any living creature, including plants and even bacteria, to be interested in life, nourishment, safety, and flourishing, and not just interested, but even obsessed (rāga). The fear and aversion with regard to harm and pain represent the flip side of bhava: vi-bhava.

It is only that, as the living being, including humans, live mobilised by these natural forces, the sensorial-emotional origination of which is well-described in the Buddha’s marvelous teaching of dependent origination, the consciousness becomes conditioned by such desire and aversion with regard to the sensorial experience and, as it finally passes away from the world, the consciousness continues naturally and according to its own bhava-powered momentum to materialise in a future being. In more simple words, that which causes rebirth is not any form of cognitive desire to be reborn, but it so happens naturally that, as the moment of death comes while there persists a desire for anything in our hearts, that desire must continue since no force exists to stop it, and then it is not the creature itself that is being reborn, but only the amalgam and sum of its cravings, aversions, fears, hopes and dreams; in a word: kamma.

This entire process of the propagation of consciousness, alike in the one life and across incalculable lives, is what bhava refers to; hence the conceptual understanding of bhava as meaning being or existence. But in experience what we perceive is not “being” or “existence”, but solely sensorial stimulation and the host of emotions they condition and, finally, our intrinsic disposition (anuyasa) to respond and react (upādāna), and to learn what to love and seek (bhavatanha), and what to fear and avoid (vibhavatanha). Rebirth happens automatically after that, because the consciousness unfolds automatically out of this process just as it already does right now as we speak.

This also means that bhava-nirodha, the ending of bhava, is not merely a stopping of the cognitive desire for rebirth, but the actual cessation of all desires without exception, liberating the consciousness from its own intrinsic natural habit (anuyasa) to relate to experience emotionally and through craving or aversion. This purification of consciousness deprives it from the bhava-fuel with which to propel and propagate itself forward in further existence. This unconditioned consciousness then vanishes and is never again materialised in any form of existence, which is what parinibbāna is.

So it is of vital importance to understand bhava as a psychological or mental experience, rather than merely as a concept; and should there remain some confusion about its psychological purport, I have found that the meditative observation of the various living beings in nature helps a lot in clarifying, intuitively, what bhava really is. Observe the dog in the following video, for example: What is it that mobilises this dog to behave in this way? What’s in it for the dog, to expend its metabolic energy on such wasteful, purposeless activity? And more over, what is it that diminishes the wellbeing and flourishing of the dog if it was to be deprived of such playful life and living? The answer is “bhava”. We ourselves, our entire existence, is nothing beyond that very activity, no self or soul exists independently from it. It is bhava that makes our consciousnesses so deeply identified with every possibility and moment of life, this life, and every one that follows thereafter.

As you’ve worded the question, it would require asserting attainment of knowledge of past lives to answer in the affirmative. Since the Buddha stresses that the teaching is immediately effective, we can all only agree on the teaching in the context of situationally different present life. Asserting a shared truth of the teaching regarding rebirth is not possible without shared experience of rebirth in the Cleopatra sense. My wife and I joke that we were both the opposite sex before (I like rom-coms and she likes Die Hard), but neither of us has concrete memories to draw upon at this time. And if ever those memories did arise, I would not feel comfortable discussing them without physical validation (i.e., seeing a former home). To do so would be unethical because of the possibility that the memories might be delusional.

Also do note that DN33 discusses the wish to be reborn as affluent, which could be satisfied by winning the lottery (which is a known cause of contemporary suffering):

‘If only, when my body breaks up, after death, I would be reborn in the company of well-to-do aristocrats or brahmins or householders!’

In the above, we have the Pali being explicit about body breaking up without use of bhavaraganusayo:

‘aho vatāhaṃ kāyassa bhedā paraṃ maraṇā khattiyamahāsālānaṃ vā brāhmaṇamahāsālānaṃ vā gahapatimahāsālānaṃ vā sahabyataṃ upapajjeyyan’ti.

From this perspective and with knowledge gained from @anon61506839’s post, I would conclude that bhavaraganusayo covers both experiences of rebirth even though most of us can only speak to the situationally different present lives as confirmation of the teaching.

Here’s a good description by Bhikkhu Bodhi:

“Bhava, in MLDB, was translated “being.” In seeking an alternative, I had first experimented with “becoming,” but when the shortcomings in this choice were pointed out to me I decided to return to “existence,” used in my earlier translations. Bhava, however, is not “existence” in the sense of the most universal ontological category, that which is shared by everything from the dishes in the kitchen sink to the numbers in a mathematical equation. Existence in the latter sense is covered by the verb atthi and the abstract noun atthitā. Bhava is concrete sentient existence in one of the three realms of existence posited by Buddhist cosmology, a span of life beginning with conception and ending in death. In the formula of dependent origination it is understood to mean both (i) the active side of life that produces rebirth into a particular mode of sentient existence, in other words rebirth-producing kamma; and (ii) the mode of sentient existence that results from such activity.”[62]

Bhava seems to mean ‘plane of existence’ (ie. 1. sensual, 2. form, 3. formless). Punabhava is rebirth- in one of those planes of existence.

What is the range of bhava? SuttaCentral

However the attraction to states of existence can be understood in the here and now.

how is there the bond of existence? Here, someone does not understand as they really are the origin and the passing away, the gratification, the danger, and the escape in regard to states of existence (bhava). When one does not understand these things as they really are, then lust for existence, delight in existence, affection for existence, infatuation with existence, thirst for existence, passion for existence, attachment to existence, and craving for existence lie deep within one in regard to states of existence. This is called the bond of existence. SuttaCentral

Bhava is very broad, and includes all of “existence”, the current life as well as future lives.

“Craving for bhava” primarily means the wish to be reborn in a future life, whether this is explicitly expressed as an aspiration to be reborn, or is more subtly an “underlying tendency” (anusaya). Either way, the root of the urge is that we are alive now and we want to keep on living. This is why I have sometimes rendered bhava as “continued existence”.

To put the same thing another way: in simple terms, craving for bhava is the wish to be reborn. When reflected upon philosophically, we can understand that that wish comes from our own attachment to this life.

That bhava has primarily a future orientation is made explicit in many places in the suttas, which frequently speak of āyatiṁ punabbhavabhinibbatti, “rebirth in a new state of existence in the future”. If you look closely at the contextual usage, it becomes apparent that this is an expanded form of the more-or-less synonymous bhava.

To specify the current life, a variety of idioms may be used: diṭṭheva dhamme, sandiṭṭhika, akālika, ānantarika, or simply idha. To specify future lives, we have samparāyika, etc.

… Another thing I found to be helpful in facilitating a more intuitive understanding of Dhamma, is to imagine how would the experience of sentient beings be like without a certain psychological phenomenon or condition that the Buddha refers to as natural or intrinsic to the living being. This seems to me to be the real purpose of the reverse enumeration of the twelve nidana. So of much interest to our discussion here is the difference between bhava-nirodha and a phenomenon such as psychogenic death, which is a mundane rather than transcendental withdrawal from bhava, and which therefore still results in rebirth!

What are the twelve nidana? I cannot find them. ![]()

It would be instructive to hear more about this distinction ![]()

Psychogenic death is an extremely unique and rare condition, where the individual, usually following some traumatic experience, loses what Schopenhauer used to call the will to life, and becomes entirely disinterested in life and living to the extent of actually dying involuntarily and without committing suicide. This bears many similarities but also marked differences with relation to the manner with which we, too, embark on a journey of estrangement and dispassion with regard to life. Theirs is a loss of every motivation, whereas our journey is driven by a spiritual motivation to realise a transcendental state of freedom. Their symptoms are characterised by numbness to pleasure and pain, whereas ours is characterised by transcendence of reactionary feelings. Theirs is a loss of consciousness and self-awareness, whereas ours is the purification of consciousness and total independence and agility of self-awareness. Such is the distinction between a mundane alienation from bhava, and a transcendental one; it is the difference between a disease caused by extreme suffering, and a healing potion that transcends suffering!

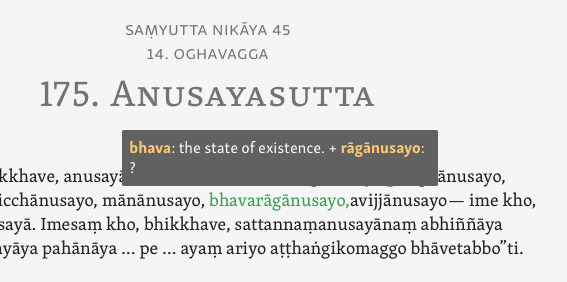

I’m having difficulty pulling this compound word apart. I get bhava and rāgā but can’t make good sense of the rest.

The final compound member is anusaya- ‘tendency, predisposition’.

Thank you

This was an excellent thread to read through!

Much mettā.

Please clarify how bhava is the answer to these questions:

What is it that mobilises this dog to behave in this way? What’s in it for the dog, to expend its metabolic energy on such wasteful, purposeless activity? And more over, what is it that diminishes the wellbeing and flourishing of the dog if it was to be deprived of such playful life and living?

Sensual lust is “Kama-taṇhā”. For example the craving for ice-cream.

I think it is the craving for continued existence generally, which could include future lives. Even an existence without ice-cream. ![]()

![]()

Delight…

…is the root of suffering. –mn1/en/bodhi

Bhava my tail, 'round 'n 'round we go.

Dogs have tails. Why do we work and pay gyms to run on their treadmills?

Thank you for the clarification!