It appears to me that your way of understanding it is that the Buddha was opposed to anything Vedic (and Sanskrit) if it were to be used as part of Buddhism. That sounds like you are attributing such ideological motivation or tribalism to the Buddha.

Your argument is that Pali in any case was closer to early-Vedic than even Classical Sanskrit, so if the Buddha were arguing in favour of Pali [a language which IMO didnt exist in his time, which in turn you’re trying to equate to a fictional Magadhabhāsā (which also IMO didnt exist), as well as to the Buddha’s own native idiom] he would not be ideologically arguing against Vedic (assuming as you do that Pali was as a whole closer, than Classical Sanskrit, to Vedic). Vedic was the Buddha’s ancestral language - and the ancestral language of almost all the people living in Magadha and all the other Mahajanapadas (except perhaps Yona and Kamboja) at that time. Such a notion of Vedic being considered ideologically brahmanical by the Buddha would be an anachronistic misconception.

As I said this account may even have been an interpolation into the Theravada vinaya (there is also the question as to whether the whole Theravāda Vinaya itself arises from the Buddha’s time or not).

The negative attitude you’ve mentioned (and the exact words used) is common to most of the vinaya prohibitions - it is not unique to this particular prohibition - the vocabulary is identical to hundreds of other prohibitions. It doesnt sound like a general aversion to Vedic being associated with himself or with Buddhism.

Stereotyping Buddhism with Prakrit and Pali and with common people - and making a imagined binary opposition with Sanskrit and Vedic culturally with Brahmins, caste system etc is a sort of binary stereotypical thinking - it tries to frame history in a particular ideological perspective and interpret every other fact through that stereotypical lens. I therefore challenge such stereotypical notions so people who take such preconceived assumptions for granted will be forced to re-examine their validity when faced with a less-stereotypical interpretation.

So there is incongruence and a certain level of implausibility in your arguments when you say Pali and Early-Buddhism are both close to and ideologically opposed to Vedic - and I generally dont agree with your reliance on authority figures (such as taking medieval commentarial & modern-academic speculation and interpretations as being an authentic historical record of the Buddha’s time and doctrines). I don’t prefer adopting arguments made by authority figures (or their imaginary consensus) uncritically - without knowing for myself how they reached such conclusions.

That is the case with all ancient texts - it is we that need commentarial explanations (as we are far removed from the time, place and culture of early-Buddhism) . But if you read modern literature (say a fiction or non-fiction book published in 2000 CE) in your native language, you wouldnt need commentaries to explain that book - would you? Your need for a commentary to understand the canon does not mean that someone living in the time and place of the Buddha would also equally need them.

Commentaries are not like oral clarifications of meanings of individual verses by teachers/senior monks. Canonical commentaries are generally codified and systematised treatises that argue for or against the views of specific traditions. They generally have a polemical intent and dont exist simply to clarify difficult part. You can read more about Indian commentarial methods and traditions from this book - Scholastic Sanskrit: A Manual for Students by Gary A. Tubb

Pali is Pali, no one is arguing that the different stages of Pali are not Pali.

However it is not homogeneous. As I said (and you perhaps disagree with this) - there was no unbroken-dialectal-continuity of Pali from stage 1 to stage 4 (as per Geiger’s classification above). Pali was not a uniform spoken language evolving naturally and dialectally across time and space. What at surface level appears to be Pali is under that surface a different language - the underlying spoken language in my opinion is a form of Old-Indo-Aryan.

Pali is an artificial construct based mainly on the epigraphic prakrit of the early inscriptions which early-Buddhists adopted initially to write down their canon (my opinion, but again you may disagree) - the 4 stages of Pali are not homogeneous, because the spoken languages underlying the 4 stages of Pali were not identical (or spoken by a single Pali ethnicity). In other words, a Canonical-Pali speaking ethnicity has never existed historically anywhere in mainland India (in my understanding).

Even at the earliest stage (the Gāthā-poetry stage), as Geiger says, there is a lot of linguistic heterogenity i.e. it is clearly not the same kind of language that exists in the prose suttas of the canon. I do not accept the argument that the linguistic archaisms of the Gāthā dialect are required for metrical reasons (as some people speculate) - as that would be like modern English poets using some archaic Middle-English or Old-English words for the sake of poetic metre. That would be a very odd thing to do when composing poetry. Classical Sanskrit poets dont use archaic Vedic vocabulary in their poetry to suit the metre - so that is not a valid argument to use for explaining the lexical and phonetic heterogenity of Gāthic Pali.

The appropriate inference to make (in my opinion) is either that the gāthā poetry originates about a century or more earlier to the prose suttas, and the prose suttas are from a later period (which would account for the phonetic and grammatical archaisms of the gāthās) - or that the prose suttas were also originally in the language of the gāthā poetry but were later artificially homogenised. My view lies between one of these two, or a mix of these two possibilities. In any case I take the gāthā poetry as a more authentic record of the earliest form of early-Buddhism than the prose suttas - due to the fact that the language and wording hasnt been tampered with as much, relative to the prose (i.e. they weren’t artificially homogenized like the prose).

You say English isn’t a homogeneous language either - but that is an apples to oranges comparison - what we expect Pali to have are one spelling per word - not two or three or four spellings for a lot of words.

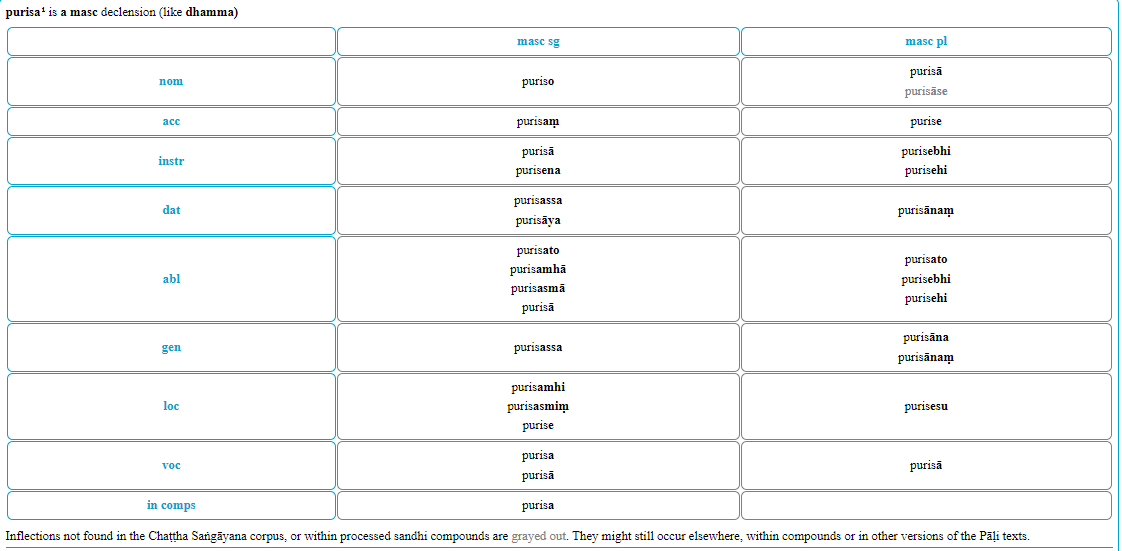

Noun declensions cannot normally have multiple word forms for each declension - but they do in Pali (there are also homonyms i.e. the same word form used in multiple declensions). Latin doesn’t have such multiple spellings or homonyms for most inflections, AncientGreek doesnt have them, Sanskrit (Classical or Vedic) doesn’t have them either - and they are all highly inflecting Indo-European languages like Pali. Pali has such forms. A single inflecting language wont show so much confusion and alternative forms naturally. See

The Pali phonetic and grammatical heterogenity in the example above is a striking contrast to the chronologically stable and consistent declensions of the same word (puruṣa) in Early Vedic (Saṃhitā texts), Middle-Vedic (Brāhmaṇa & Āraṇyaka texts), Upaniṣads, hundreds of Classical Sanskrit texts, and its sub-varieties such as Sutra Sanskrit (of the various Śrauta-sūtras, Gṛhya-sūtras, Sulba-sūtras, Dharma-sūtras etc associated with each Veda-śākhā), Epic Sanskrit (of the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata), Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit texts, Jain Sanskrit texts etc :

| Masculine | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | puruṣaḥ | puruṣau | puruṣāḥ |

| Vocative | puruṣa | puruṣau | puruṣāḥ |

| Accusative | puruṣam | puruṣau | puruṣān |

| Instrumental | puruṣeṇa | puruṣābhyām | puruṣaiḥ |

| Dative | puruṣāya | puruṣābhyām | puruṣebhyaḥ |

| Ablative | puruṣāt | puruṣābhyām | puruṣebhyaḥ |

| Genitive | puruṣasya | puruṣayoḥ | puruṣāṇām |

| Locative | puruṣe | puruṣayoḥ | puruṣeṣu |

Apart from these in many cases the Pali spellings dont always follow the expected sound-laws of Pali. I mentioned several dissimilar consonant clusters, (for example, see here) that exist in Pali but shouldn’t, as they violate normative Pali phonetics & sound-laws.

Besides, back in the Buddha’s era, the world was not as globalised as it is now, the Indo-Aryan speakers were not as exposed to such a diversity of cultures and languages that modern speakers of English are exposed to. Pali would not have naturally acquired such a linguistic diversity that you associate with globalised English.

Most of the heterogenity in early-Pali (in my opinion) arises from

- a general non-adherence to pre-existing grammatical and phonetic standards (i.e. the phonetic and grammatical standards that apply to and characterise Early-Vedic, Middle and Late-Vedic / Classical Sanskrit), and

- an attempt at artificial phonetic & grammatical simplification from Old-Indo-Aryan to make it suitable for easy writing in the early Brahmi and early-Kharoshthi scripts, and

- An attempt to approximate the epigraphic language of the early inscriptions, by adopting their orthographic & morphophonetic norms in the Pali canon.

So this unique sort of heterogenity was not mainly dialectal in nature - i.e. it doesn’t arise from a mix of dialects. It arises from a mix of the 3 causes mentioned above. However genuine dialectal differences also do exist in Canonical Pali, but they are a relatively minor issue (and similar dialectal differences exist within Classical sanskrit of the same period too) - so dialectalism is not the core distinguishing factor between Classical Sanskrit and Pali.

But I’m not talking about the possible historicity of ‘any such event’ (in whatever form). We can speculate whether such a council was held, who called for it to be held, when and where it was held, who attended or didnt attend, what was discussed or not discussed, what decisions were made, etc. All those issues would be educated guesses at best - because we dont have any eyewitness or early description about it in any extant literature.

I’m speaking specifically about the the description of the first council narrated in the commentarial texts - and the idea that a full canon (as we have it now) along with full commentaries - all existed in our Pāli and was recited in that council by specific named elder monks like Ānanda, Upāli etc - this narrative is undoubtedly a figment of the commentator’s imagination and is ahistorical. Nobody to my knowledge accepts the commentarial narrative as an accurate and exact depiction of history. The names you mentioned, like archaeologist Louis Finot, Indologist E. E. Obermiller, are 19th and early 20th century scholars who died over 100 years ago. Is anybody still citing those early scholars that you talk about or their reliance on the commentarial account as being true?

I am happy to accept Buddhaghosa as the voice of the Srilankan Theravada tradition (or even the whole Theravada tradition since the 6th century CE). I am happy to accept that what Buddhaghosa says is what the Theravadins of his time considered real and traditional.

But if you want me to accept that Buddhaghosa and the Theravada tradition (as per its commentaries), and the Pali language, are representative of Buddhism as a whole or the history of Buddhism and the Buddha as a whole - I can’t agree with that conclusion. Buddhaghosa and the Theravada tradition present their own perspective and beliefs of early Buddhism. Historically the Pali canon originates within the world of early-Buddhism (but not pre-sectarian early Buddhism). The Pali canon already shows a Theravada slant in some parts - and the fact that it doesnt show any variation in language i.e. it doesnt show anybody (not even Vedic Brahmins) as speaking in Sanskrit - and it converts all early Vedic deity names and Ṛṣi names to Pāli - means that it is not a 100% authentic representation of the time and culture of the Buddha. I have my doubts if the Pāli canon is even depicting historical early Buddhism 100% accurately, but its depiction of non-Buddhist traditions is decidedly inaccurate and one-sided.

So the Theravada commentaries only speak for the beliefs and traditions of the mid-1st millenium CE Theravada tradition. Most of the Pali canon only speaks of the circa 3rd or 2nd century BCE world of the Pali tradition of early Buddhism. Neither of them can be treated as a 100% authentic (or even 90% authentic) voice of the historical Buddha - in my personal opinion. I acknowledge you have a different view about this - and our views may not meet for the foreseeable future - but that’s OK.

I dont consider many of them plausible - they are opinions I have already seen before in the arguments of others - I have processed them mentally and find them untenable for various reasons (as I have explained above in detail).

I come from an Indian cultural background, and I have an immersive emic understanding of my native culture and its historical bearings. I speak and understand several modern Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages. I speak a modern version of Sanskrit, and I work on historical Sanskrit and Pali original texts, and I read frequently about the other Prakrits and early inscriptions as well. My perspectives on certain issues are informed by this cultural background - and I am not as much reliant on academic arguments for my understanding of my culture and its history as you may probably be.

If theories put forth by academia dont convince me, I am able to argue based on my emic understanding of Indian culture, history and historical literature. If you have a similar cultural and linguistic background as me - we may probably have an agreement or come to similar views of historical issues - but on the other hand, you now have your own unique perspectives based on your studies of Pali texts and reliance on secondary and tertiary research - my objective is not to change your thinking but offer my perspectives (and see where the similarities and differences in our thinking lie). I completely acknowedge your take on things (and I respect your knowledge of Pali and Buddhism) and thank you for sharing your perspectives and understanding - but if I dont accept your logic, beliefs or interpretation of facts, we should let that be.