I’m not sure if you’ve read this thread but the question asked by the poster is similar in nature to yours. There is a response here from Bhante Sujato were he is relating a story told by a lay disciple who was on a meditation retreat.

https://discourse.suttacentral.net/t/an3-63-walking-in-4th-jhana/6633/5

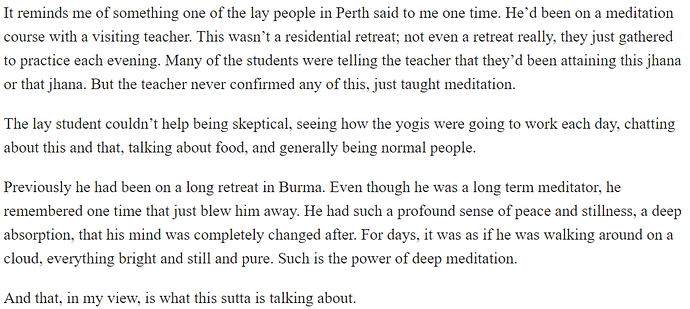

Here is the snippet if you don’t want to read the whole post.