The suttas mention a group of Vedic sacrficies that were condemned by the Buddha as being especially violent. These include the human sacrifice, horse sacrifice, sammāpāsa, vājapeya, and niraggaḷa.

I’m trying to figure out exactly what these mean.

Sammāpāsa is not a regular name of a Vedic sacrifice. The Pali commentaries explain it as a sacrifice held after the “throwing” (pāsa) of a “peg” (samma). They say this is held at the Sarasvati river. This detail is confirmed in the Brahmanical side, as the Bhāgavata Purāṇa says that śamyāprāsa is a hermitage on the banks of the Sarvasvati.

For one it is a hermitage, for another a sacrifice, but the Saravasvati is a common detail.

The Sanskrit dictionaries confirm the sense of “peg-casting”. MW says the sense is the same as śamyākṣepa, “the cast of a staff, distance that a staff can be thrown”.

On one level, this is sort of clear. It’s a sacrifice where a peg of wood is cast, then the altar is set up and the sacrifices held there.

Why though? What’s the root of it all? And why is it connected with the Sarvasvati—which had already dried up long before the Buddha—when the Buddhist texts clearly treat it as a general and ongoing practice?

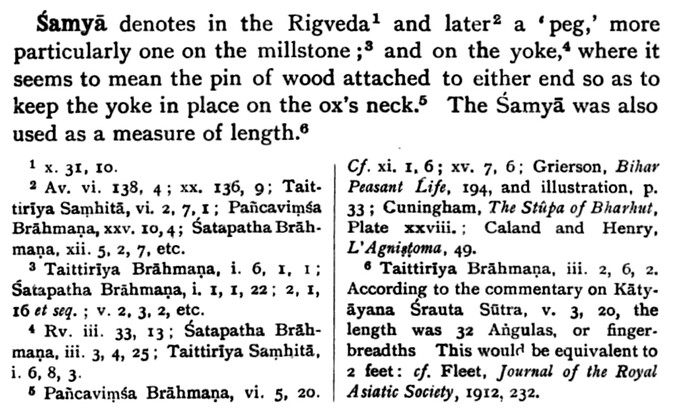

More useful information comes from the Vedic Index:

The relevant portion is here:

This gives us a good idea of the functional purpose of the śamyā. It is not just any old peg, but is that which holds the yoke together. The yoke (yoga) is of course of central practical and metaphorical significance for the Brahmanical tradition. To remove the śamyā is to release the yoke.

Now, the yoke was a critical part of the old Indo-European culture, a nomadic pastoral culture for whom the yoke on the horse, the cow, and the ox defined their lifestyle. Witzel has shown that one of the crucial cultural ideas is that of the khema or yogakkhema, the place of sanctuary where the yoke is released at the end of the day’s journey. The khema was something like a “sanctuary” or an “oasis”, where man and beast could rest in harmony.

There’s another interesting detail in the Vedic Index. It says it is sometimes used as a measure of length.

In the Vinaya, length is sometimes determined by the throw of a clod or a stone. The “vicinity” of a village or other inhabited area is a “stone’s throw” of an average man (majjhimassa purisassa leḍḍupāto). This tells us that a “throw” was not only a measure of length, but that this was used to define the territory associated with a habitation. In other words, it helped to mark out territory.

Obviously this doesn’t agree with the śamyā being a length of about two feet, as cited above. But remember that MW said it was the distance a peg could be cast. I don’t know, maybe it’s a red herring or maybe the same name was used for different dimensions?

Regardless of whether the śamyā itself was a measure of the throw, what if the sammāpāsa began in a similar way? At the end of a journey, when the beasts were unyoked, the “peg” from the yoke was “tossed” as a symbolic way of saying “we’re not driving any further”, establishing authority over this piece of land. This would agree with other sacrifices in the prohibited list, such as the horse sacrifice, which is specifically in order to establish royal authority over territory.

It would also make sense of why śamyāprāsa became known as a specific place on the Sarvasvati. It could have been a place that was originally marked out by the sammāpāsa ritual, and its name was secondarily derived. It could even have been one of the early stopping places for the Indo-European peoples. In any case, if sammāpāsa as the name of a place is secondary, it would make better sense why the suttas treat it as a regular ritual. It would also make sense of why the ritual is little known or entirely forgotten in Vedic circles, as its roots in pastoral nomadism became irrelevant.

Pulling this together, I propose the following. The sammāpāsa originated as a rite among the wandering Indo-European pastoralists. At the end of a day’s journey, when they wished to establish a settlement, they would unyoke their cattle and horses. Pulling out the yoke-pins, they cast them as far as they could and claimed the area as theirs. They celebrated their claim with the slaughter of a beast and a feast shared among the people. Over time, this evolved into a formal ritual for establishing authority over an area, sanctified with a sacrifice. A particular hermitage on the Sarasvati became known for being established in this way. As the nomadic lifestyle was abandoned, however, the purpose and meaning of the ritual was forgotten, and it almost entirely faded from view, remembered only in Buddhist texts and a few scattered references.

In a way, it could be regarded as a self-negating ritual. Its very success in establishing fixed settlements led to its demise.

This is all very speculative, and before taking it seriously, it would be important to check the various references, especially those mentioned in the Vedic Index. Unfortunately I have neither the time nor the ability to do that.