Continuing the discussion from Some issues with the Chinese texts:

Here’s a very nice essay on the Chinese canons by user @llt . The original is on his website, Lapis Lazuli texts.

Chinese Buddhist Canons

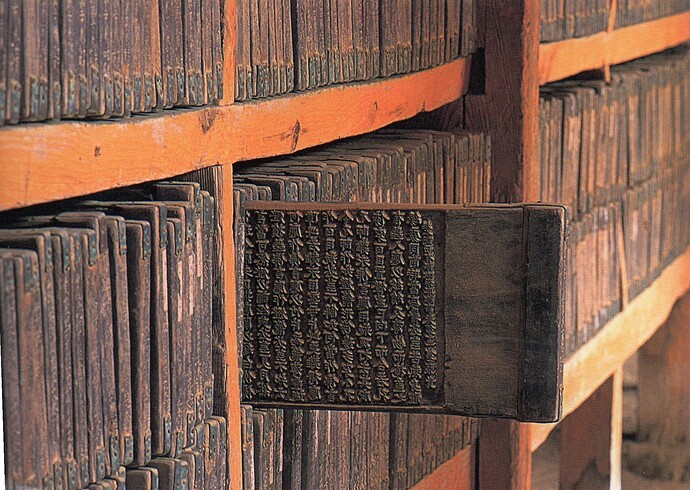

Of the major Buddhist traditions, the Chinese Buddhist canon historically represented the largest collection of Buddhist texts, spanning from early Buddhist texts all the way up to late era decline of Buddhism in India. While Indic texts mainly deteriorated due to materials and storage conditions, China developed woodblock printing and began compiling and printing enormous canons of all major translated texts, along with discourses, histories, commentaries, and other supplements.

Over the centuries, Chinese Buddhist canons remained fairly constant in their format and use of printing technology. Woodblock printing continued to be used until the modern era simply due to the very large number of Chinese characters required for printing. With so much effort required to use movable type, there was little impetus to develop the required technology to do so.

Most major Chinese Buddhist canons were compiled and published by the imperial court of China. This was done in part to develop merit for the entire country, and to uplift the culture. Several emperors were especially interested in the development of Buddhist canons, and in some cases keenly oversaw many details related to their organization and publication.

Today several of these canons are still available to us, including the Tripiṭaka Koreana, the Qianlong Tripiṭaka, and the Taishō Tripiṭaka, among others. Efforts are also underway to develop complete and accurate electronic canons, and this seems to be the future of the Chinese Buddhist canon. What follows are several of the most important Chinese Buddhist canons, including some basic notes about their history and organization.

Tripiṭaka Koreana 高麗大藏經

The Tripiṭaka Koreana (goryeo daejanggyeong 高麗大藏經) is a 13th-century canon printed by the Goryeo dynasty in Korea. The original canon was carved in 1087 during a turbulent period in which the Goryeo dynasty was trying to defend its territory from Khitan nomads. The canon was carved in order to gain the necessary merit which might protect Korea from the Khitan.

When the Mongols invaded Korea in 1232, the original set of woodblocks was completely destroyed by fire. In order to ensure protection from the Mongols, King Gojong ordered for the canon to be carved once again. The canon was started in 1236 and was completed in 1251, and took a total of sixteen years to carve.

The original 81,258 woodblocks remain intact today in good condition, and are regarded as accurate and faithful reproductions of the Chinese Buddhist canon. The canonical translations are divided mainly into two literal tripiṭakas: a Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka and a Hīnayāna Tripiṭaka, each containing the three classical divisions of Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma.

- 大乘三藏 Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka

- 大乘經 Mahāyāna Sūtra

- 般若部 Prajñāpāramitā (1–21)

- 寶積部 Ratnakūṭa (22–55)

- 大集部 Mahāsannipāta (56–78)

- 華嚴部 Avataṃsaka (79–104)

- 涅槃部 Parinirvāṇa (105–110)

- 五大部外諸重譯經 Other Major Sūtras (111–387)

- 單譯經 Minor Sūtras (388–522)

- 大乘律 Mahāyāna Vinaya (523–548)

- 大乘論 Mahāyāna Abhidharma

- 釋經論 Sūtra Commentaries (549–569)

- 集義論 Collected Treatises (570–646)

- 大乘經 Mahāyāna Sūtra

- 小乘三藏 Hīnayāna Tripiṭaka

- 小乘經 Hīnayāna Sūtra

- 阿含部 Āgama (647–800)

- 單譯經 Minor Sūtras (801–888)

- 小乘律 Hīnayāna Vinaya (889–942)

- 小乘論 Hīnayāna Abhidharma (943–978)

- 小乘經 Hīnayāna Sūtra

- 賢聖傳記錄 Records of the Noble Ones

- 西土賢聖集 Sages of the West (979–1046)

- 此土撰述 Writings of This Land (1047–1087)

- 宋續入藏經 Song Period and Later Additions (1088–1498)

Yongle Northern Tripiṭaka 永樂北藏

The Yongle Northern Tripiṭaka (yongle beizang 永樂北藏) was the most important Chinese Buddhist canon carved in the Ming dynasty. It was named after the Yongle Emperor who commissioned it and guided the publication process.

The Yongle Northern Tripiṭaka was preceded by the Yongle Southern Tripiṭaka (yongle nanzang 永樂南藏). The Southern Tripiṭaka was carved in the capital of Nanjing. The project was started in 1409 and ended around 1419. When the capital was moved from Nanjing to Beijing, a new canon was carved in Beijing, which became the Northern Tripiṭaka. The project was started in 1419 but was not finished until 1440. The two canons are similar, but the Northern Tripiṭaka is regarded as being more definitive, and having fewer mistakes.

The Yongle canons were among the first major Chinese Buddhist canons to adopt a conservative organizational principle. Previously, popular canons had divided translations primarily into Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna, each having its own divisions of Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma. Hence, in these earlier canons, such as the Tripiṭaka Koreana, it is perfectly sensible to speak of a “Hīnayāna Tripiṭaka” and a “Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka.” The revised approach was to make one single Tripiṭaka incorporating the texts of both vehicles. Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma were the principle divisions, each divided into Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna genres.

The following is the outline of the Yongle Northern Tripiṭaka.

- 經藏 Sūtra Piṭaka

- 大乘般若部 Mahāyāna Prajñāpāramitā (1–35)

- 大乘寶積部 Mahāyāna Ratnakūṭa (36–74)

- 大乘大集部 Mahāyāna Mahāsannipāta (75–102)

- 大乘華嚴部 Mahāyāna Avataṃsaka (103–133)

- 大乘涅槃部 Mahāyāna Parinirvāṇa (134–148)

- 大乘五大部外重譯經 Mahāyāna Other Major Sūtras (149–399)

- 大乘單譯經 Mahāyāna Minor Sūtras (400–567)

- 小乘阿含部 Hīnayāna Āgama (568–708)

- 小乘單譯經 Hīnayāna Minor Sūtras (709–812)

- 宋元入藏諸大小乘經 Song–Yuan Added Sūtras (813–1050)

- 宋元入藏諸大小乘經之餘 Song–Yuan Added Sūtra Extras (1051–1113)

- 律藏 Vinaya Piṭaka

- 大乘律 Mahāyāna Vinaya (1114–1138)

- 小乘律 Hīnayāna Vinaya (1139–1207)

- 論藏 Abhidharma Piṭaka

- 大乘論 Mahāyāna Abhidharma (1208–1305)

- 小乘論 Hīnayāna Abhidharma (1307–1353)

- 宋元續入藏諸論 Song–Yuan Added Abhidharma (1354–1377)

- 撰述 Records

- 西土聖賢撰集 Sages of the West (1378–1525)

- 此土著述 Writings of This Land (1526–1712)

- 大明續入藏諸集 Great Ming Tripiṭaka Added Works (1715–1757)

- 附入南藏函號著述 Works Attached to the Southern Canon (1758–1766)

Jiaxing Tripiṭaka 嘉興大藏經

The Jiaxing Tripiṭaka (jiaxing dazangjing 嘉興大藏經) is a canon first printed in China during the early Qing dynasty. The woodblock carving for this canon began in 1579 during the Ming dynasty, but the work was not completed until nearly a hundred years later in 1677. Unlike some other famous collections, the Jiaxing Tripiṭaka was not undertaken as a government project. Instead it was compiled and printed as a private effort by monastics. The project began in Shanxi province on Mount Wutai, the bodhimaṇḍa of Mañjuśrī, but it was later moved to a temple in Jiaxing, near the eastern coast.

The Jiaxing Tripiṭaka is extraordinary among Chinese Buddhist canons because it contains over five hundred works not found in any other extant collections. These added texts are mostly medieval works affiliated with the Chan school of Buddhism, and leave behind rich records of centuries of study and practice. Due to its unique position among the canons, the Jiaxing Tripiṭaka is regarded as a valuable supplement to other canons.

Qianlong Tripiṭaka 乾隆大藏經

The Qianlong Tripiṭaka (qianlong dazangjing 乾隆大藏經), is an 18th-century canon printed in imperial China by the Qing dynasty during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor. The project started in 1733 and finished in 1738, taking only five years. The Qianlong Tripiṭaka was the last Chinese Buddhist canon printed in China in the classical style. As such, its typography and lack of punctuation preserve the original style of the Chinese Buddhist texts without any modern additions.

The Qianlong Tripiṭaka is also commonly called the Longzang 龍藏, or the “Dragon Store.” In the view of Mahāyāna Buddhism, the serpentine nāgas 龍 are the keepers and bestowers of the Buddhist sūtras. Their own libraries, hidden in their underwater kingdoms, are said to be much more vast than any Buddhist canons of the human realm. The nāgas are regarded as largest and most complete Buddhist canon, which the Longzang aims to reflect.

- 經藏 Sūtra Piṭaka

- 大乘般若部 Mahāyāna Prajñāpāramitā (1–19)

- 大乘寶積部 Mahāyāna Ratnakūṭa (20–56)

- 大乘大集部 Mahāyāna Mahāsannipāta (57–82)

- 大乘華嚴部 Mahāyāna Avataṃsaka (83–108)

- 大乘涅槃部 Mahāyāna Parinirvāṇa (109–121)

- 大乘五大部外重譯經 Mahāyāna Other Major Sūtras (122–371)

- 大乘單譯經 Mahāyāna Minor Sūtras (372–537)

- 小乘阿含部 Hīnayāna Āgama (538–674)

- 小乘單譯經 Hīnayāna Minor Sūtras (675–776)

- 宋元入藏諸大小乘經 Song–Yuan Added Sūtras (777–1076)

- 律藏 Vinaya Piṭaka

- 大乘律 Mahāyāna Vinaya (1077–1101)

- 小乘律 Hīnayāna Vinaya (1102–1160)

- 論藏 Abhidharma Piṭaka

- 大乘論 Mahāyāna Abhidharma (1161–1253)

- 小乘論 Hīnayāna Abhidharma (1254–1290)

- 宋元續入藏諸論 Song–Yuan Added Abhidharma (1291–1313)

- 撰述 Records

- 西土聖賢撰集 Sages of the West (1314–1460)

- 此土著述 Writings of This Land (1461–1669)

- 大清三藏聖教目錄 Great Qing Tripiṭaka Index of the Noble Teachings (1670)

Taishō Tripiṭaka 大正新脩大藏經

The Taishō Tripiṭaka (taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經) is now the most common Chinese Buddhist canon, and was originally compiled and printed in Japan in the early 20th century. The project started in 1924 and was completed in 1934, lasting ten years. Other previous canons were used for comparison, including the Tripiṭaka Koreana, and various canons of the Song and Ming dynasties.

The Taishō Tripiṭaka used more modern technology and ideas. Scholars, now more aware of exact genres of Buddhist texts, wished to organize them into more precise categories. The conservative organization into a three-part Tripiṭaka, as seen in the Qianlong Tripiṭaka, was flattened into many genres. New typographic standards were applied as well, and all texts received some minimal punctuation with the full stop 。This punctuation was sometimes made without careful regard for the text in question, and is sometimes erroneous. Nevertheless, the Taishō Tripiṭaka remains the most common and important Chinese Buddhist canon, and the starting point for modern electronic canons.

- 阿含部 Āgama (1–151)

- 本緣部 Jātaka (152–219)

- 般若部 Prajñāpāramitā (220–261)

- 法華部 Saddharma Puṇḍarīka (262–277)

- 華嚴部 Avataṃsaka (278–309)

- 寶積部 Ratnakūṭa (310–373)

- 涅槃部 Parinirvāṇa (374–396)

- 大集部 Mahāsannipāta (397–424)

- 經集部 Collected Sūtras (425–847)

- 密教部 Esoteric Teachings (848–1420)

- 律部 Vinaya (1421–1504)

- 釋經論部 Sūtra Explanations (1505–1535)

- 毗曇部 Abhidharma (1536–1563)

- 中觀部類 Mādhyamaka (1564–1578)

- 瑜伽部類 Yogācāra (1579–1627)

- 論集部 Collected Śāstras (1628–1692)

- 經疏部 Sūtra Clarifications (1693–1803)

- 律疏部 Vinaya Clarifications (1804–1815)

- 論疏部 Śāstra Clarifications (1816–1850)

- 諸宗部 Sectarian Works (1861–2025)

- 史傳部 History (2026–2120)

- 事彙部 Cyclopedia (2121–2136)

- 外教部 Outer Paths (2137–2144)

- 目錄部 Catalogues (2145–2184)

- 續經疏部 Sūtra Clarifications of Japan (2185–2700)

- 悉曇部 Siddhaṃ Script (2701–2731)

- 古逸部 Ancient (2732–2864)

- 疑似部 Doubtful (2865–2920)

- 圖像部 Illustrations

- 昭和法寶 Shōwa Era Dharma Treasury

- 總目錄 Index

Electronic Buddhist Canons

Among the Chinese Buddhist canons, the Taishō Tripiṭaka is especially important because it is the only canon to be digitized and made widely available to the public. The SAT Daizōkyō Text Database and the Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association (CBETA) both make the canon freely available on their websites.

The CBETA Dianzi Fodian (CBETA 電子佛典) is the most open project, and their electronic canon is available in downloadable forms including in open formats such as TEI XML. They have also begun a larger effort to begin digitizing other canons and comparing them with their CBETA electronic canon. The goal of the project is not just a digitization of the Taishō Tripitaka, but a full revision of the canon in light of past canons and other available texts, such as the Tripiṭaka Koreana and various canons of the Ming and other dynasties.

when compared to the Pali Canon, which is like the size of the earth

when compared to the Pali Canon, which is like the size of the earth  . But if you think the Pali Canon is already huge, just like the

. But if you think the Pali Canon is already huge, just like the  , then the Chinese Canon is probably like the

, then the Chinese Canon is probably like the  . But bigger size doesn’t matter really, I just stated the fact.

. But bigger size doesn’t matter really, I just stated the fact.