Some very interesting discussions here, and I’m sorry I can’t contribute more, but just on a couple of details.

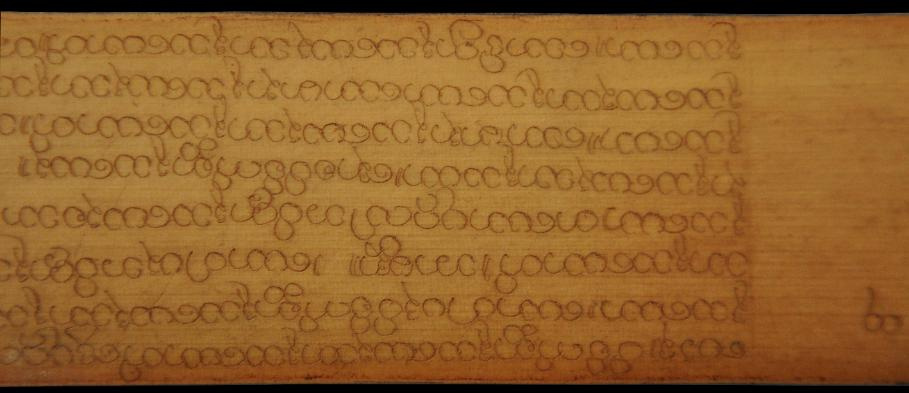

There might be some punctuation; even in Brahmi there is punctuation. Devanagari uses | and ||. However manuscript editions would use little or no punctuation. Here’s a closeup of a Burmese palm leaf manuscript.

No real punctuation. Manuscripts typically didn’t even observe line-ending conventions. They just broke the word whenever they ran out of space.

Early printed editions quickly adopted western punctuation conventions. See here a page from the Rama 5 edition of Thailand, late 19th century.

It uses quote marks, paragraphs, and so on. These are added at the editor’s discretion. I am currently working closely with the Mahasangiti edition, which on the whole is probably the best edited of any modern Pali text. However there are still quite frequent punctuation errors and inconsistencies.

Sometimes, yes. We can only know after checking the specifics. In a case like this, we need all the help we can get, and both the pre-Buddhist texts and the Chinese are useful.

But to answer your question, nāmarūpa is a pre-Buddhist term, and in fact it is clearly used by the Buddha in response to and critique of Brahmanical ideas. The Kevaddha Sutta itself is one example of this.

To put yourself in the brahmins’ shoes, think of it something like this. The rūpas are the diverse manifest forms that appear in the world; the “things”, if you will. The nāma are the “names” we give to those forms; i.e. the inner concepts that map onto the external realities.

These are felt to have a fundamental connection. This connection is, in fact, the basis of magic. By naming something or someone, you have a power over it. A name, in other words, is not just an arbitrary symbol assigned to something (as held by Buddhists and by science) but is part of its essence.

The brahmins believed that language—real language, i.e. Vedic Sanskrit—was created by the divinity; more, it is the living expression of divinity in the world. This belief system dominated older Brahmanical thought.

Not long before the Buddha, however, a new generation of more sophisticated philosophers arose, most importantly Yajnavalkya, and the made a radical new proposal. All the “forms” of the world and their corresponding “names” are in reality just expressions of the underlying divinity, which is the true self, i.e. consciousness (vijnāna). Just as all the individual rivers, with their specific “shapes” and “names” disappear when they merge into the ocean, so too all the individual “names” and “forms” which we mistakenly (neti! neti!) take to be our self disappear when they return to the ocean of vijnāna.

Thus we no longer merely participate in the expression of divinity (by reciting Vedic texts), we become that divinity (by meditative absorption in infinite consciousness).

The Buddha’s teachings are specifically phrased as a refutation of these views. This is why he emphasizes that viññāṇa and nāmarūpa are interdependent, and equated Nibbana with the cessation of consciousness.

on p. 65 (see the picture below).

on p. 65 (see the picture below).