One of the most celebrated verses of the Therigatha sees the nun Muttā celebrate her freedom in decidedly feminist verses (Thig 1.11). They are usually translated something like this:

I’m freed, well-freed,

freed from the three crooked things:

the mortar, the pestle,

and my crooked husband.

There’s one little problem with this rendering. Here is a mortar and pestle:

Notice something? They’re not crooked! What’s going on here: was Muttā simply unable to choose an apt simile? Let us see!

Now, this verse echoes a much less-known verse by the monk Sumangala at Thag 1.43. there he speaks of three crooked things: sickles, ploughs, and hoes. Here’s what they look like.

Sickle:

Plough:

Hoe:

They’re all crooked! So that settles that. Obviously the monk was able to use a metaphor in an appropriate way, but the nun wasn’t.

Or! Maybe she was doing something a little more subtle.Maybe she was making a sly remix of the original verses, using the metaphors to express a reality that would have been well understood by her fellow nuns.

My admittedly incomplete researches have not yet unearthed any discussion of this problem. But a solution is suggested in the commentary, which says that when grinding grain in the pestle with the mortar, one becomes bent over, so these things are called “crooked” because they make you crooked (khujjakaraṇahetutāya tadubhayaṃ ‘‘khujja’’nti vuttaṃ). The commentary says that, on the other hand, the husband was indeed humpbacked, and he may well have been. But that doesn’t necessarily exhaust the simile.

For the verse as a whole is, of course, about sex. The action of the mortar and pestle needs no explaining; it’s an obvious metaphor for sex. And that a women would be forced to be bent over for the sexual needs of her husband is a clever extension of the “crooked” metaphor. The act of sex, performed unwillingly as an obligation of marriage, is felt as demeaning and lessening, just another domestic grind.

In a literature as large and ancient as that of India, it is rare to find an idea or simile that is completely unique. Thus Monier-Williams tells a founding myth from the Mahabharata of the city known in Pali as Kaṇṇakujja and in Sanskrit as Kanyakubja:

The current etymology (kanyā-,“a girl”, shortened to kanya,and kubja, “round-shouldered or crooked”) refers to a legend in Rig Veda 1.32.11 [Note: I cannot find this], relating to the hundred daughters of Kuśanābha, the king of this city, who were all rendered crooked by Vāyu [the wind god] for non-compliance with his licentious desires.

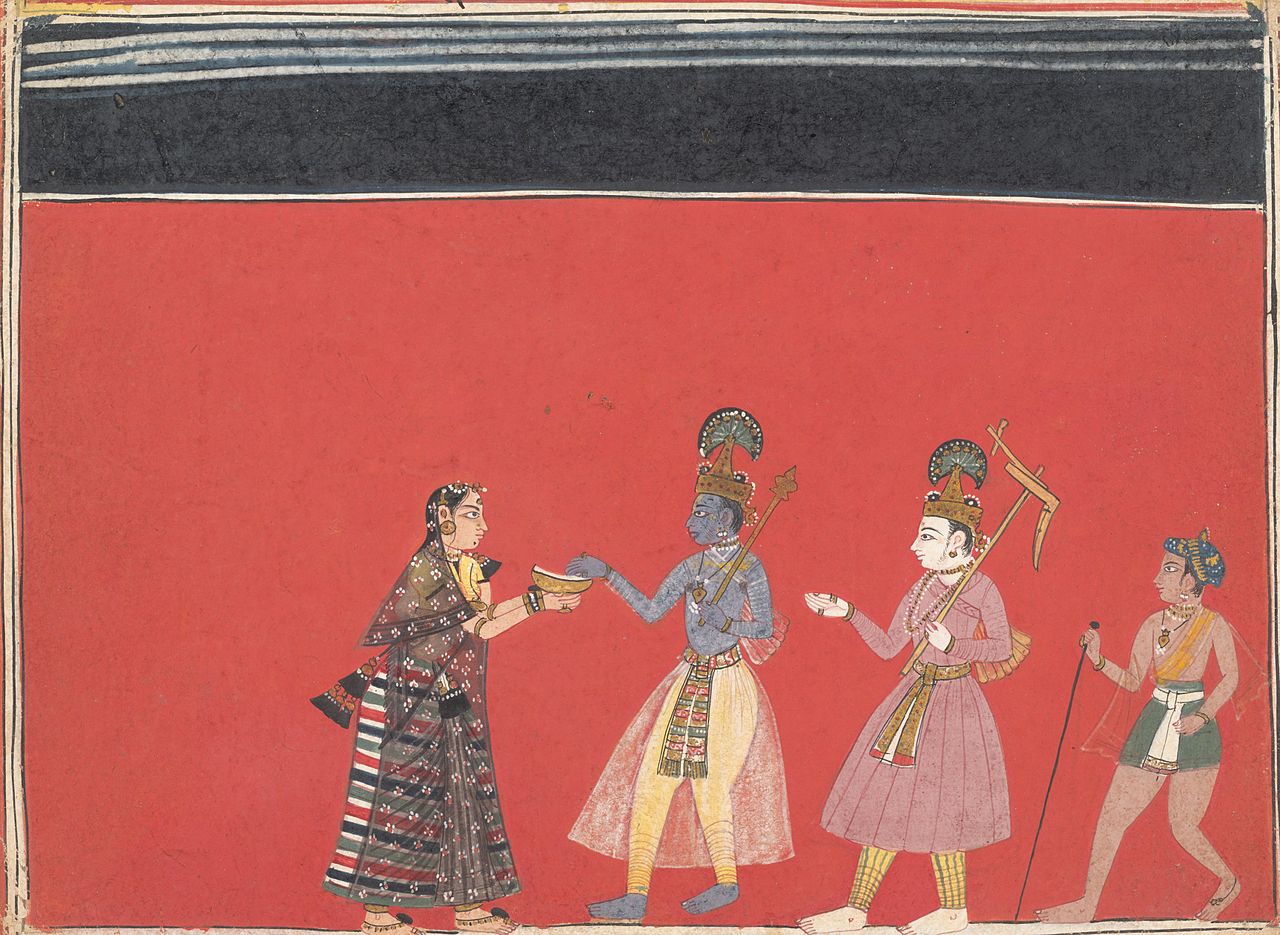

The Hindu deity Kubjā, furthermore, is described in the Bhagavata Purana and elsewhere as a humpbacked women who meets Krishna and Balarama. When she gifts Krishna a medicine, he rewards her by straightening her “triple deformity” and revealing her in her true beauty. She immediately attempts to seduce Krishna, but is refused.

There is a pattern here, an allusive and allegorical one to be sure, about men and women, compliance and consent in sex, and the physical crookedness that makes the husband repulsive, or else, perhaps, makes the wife feel repulsive for complying.

I propose a rendering like this:

I’m freed, well-freed,

freed from the three things that bent me down:

the mortar, the pestle,

and my humpbacked husband.