Let’s look at a subtle aspect of dependent origination: how it encapsulates a nascent theory of developmental psychology.

We’re going to be focusing on two main suttas: DN 15 Mahānidāna “The Great Discourse on Causation”, and MN 38 Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya “The Longer Discourse on the Ending of Craving”. In addition, we’ll glance at the standard analysis of the 12 factors found in SN 12.2 Vibhaṅga.

These texts introduce a more detailed and organic depiction of dependent origination, especially the sequence around birth, compared to the more abstract presentation commonly found.

MN 38 describes the process of conception in terms borrowed from the brahmins. Conception here is gabbhassāvakkanti, where avakkanti indicates the “conception” of the baby. Avakkanti, alternatively spelled okkanti, is one of the stock synonyms for jāti i.e. “rebirth” in SN 12.2.

Conception is held to take place with three factors, two of which are physical—sexual intercourse and the woman being in her fertile cycle—as well as the presence of the somewhat mysterious gandhabba. This is an interesting usage here, but I’ll pass over it for now. In the Buddhist traditions it is always explained as equivalent to “consciousness”, i.e. viññāṇa.

The text then speaks of the pain endured by the mother as she bears her child for nine or ten months, followed by the pain of giving birth, all of which is very risky. The word for “giving birth” is vijāti.

DN 15 describes the same process in a slightly different way. There it speaks of consciousness being conceived (again okkanti) in the mother’s womb, and the “coagulation” of name and form. I think the unusual word samuccissatha arises from the ancient view that the embryo is formed from the “coagulation” of the semen and the menstrual blood. Lacking knowledge of sperm and ovum, this isn’t too inaccurate a description.

Again the risks of pregnancy are emphasized, as DN 15 speaks of the possibility of a miscarriage (vokkamati) after conception. Were this to take place there would be no birth, here described as abhinibbatti, which is another of the stock synonyms for rebirth in SN 12.2. The arrival into “this state of existence” (itthatta) uses the same term commonly applied to the arahant, who will not be reborn into “this state of existence”.

So in these different accounts, we see a number of shared features. Linguistically, there is a common vocabulary. That’s hardly unusual, since they are talking about the same thing. What is more significant is the emphasis on the mother’s burden, and the dangers of the process of childbirth. Obviously this was, and remains, a sad reality for women today.

The dangers do not stop at birth, for DN 15 goes on to say that it is also possible that the boy (kumāra) or girl (kumārikā) might die (vocchijjati, “be cut off”) while still young (dahara), before growing up (vuddhiṁ virūḷhiṁ vepullaṁ āpajjati). In both cases—miscarriage and death of an infant—it says that “name and form” will not continue, i.e. the cycle of dependent origination is cut off there.

This shows us that the full process of dependent origination need not be complete in a single life. In the case of one who dies too young, the process is cut short. In such a case, since the infant is too young to have made any significant kamma in this life, their rebirth will be determined by their kamma from past lives.

But what happens if the baby survives pregnancy and infancy? This is taken up in MN 38. The boy—while DN 15 speaks of boys and girls, in MN 38 only boys are mentioned—grows up and his sense faculties mature. The word for “growing up” (vuddhi) is applied to the “boy” here just as it was applied to “name and form” in DN 15: obviously they are talking about the same thing.

What’s interesting is that at this point, the child plays “childish games” with toys, including such things as toy carts and toy boys. The thing about such games is that they’re not real. If you shoot a toy bow, you don’t harm anyone. A child playing is not making kamma in the same way that an adult does when they use the real thing. So at this point the process is still incomplete.

The boy then grows further, and their sense faculties mature further, until they enjoy themselves with the five kinds of sensual stimulation. The text isn’t clear about the exact time frame here, but clearly the individual is becoming an adult. The text is marking out a couple of signposts in the developmental process. In any case, now their six senses (saḷāyatana) are mature. This is the factor that arises after “name and form” in dependent origination.

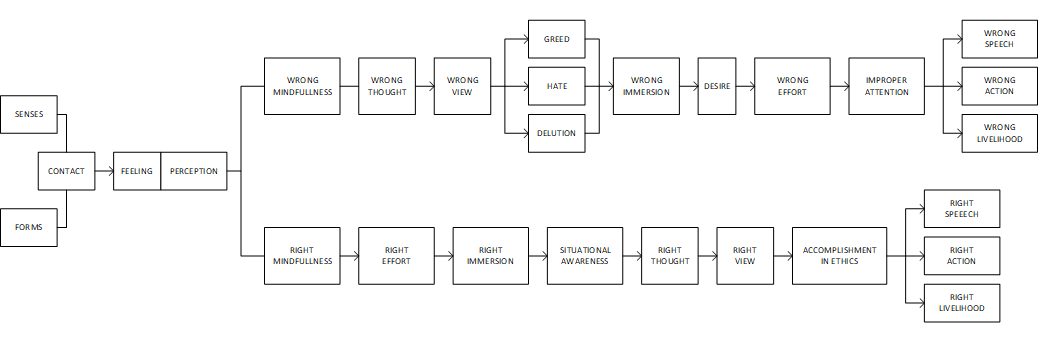

Next they are said to experience sensual stimulation through these senses, starting with sight. This is “contact” (phassa), which arises after the six senses. Experiencing “contact” with sensual stimuli gives rise to pleasant and unpleasant feelings (vedanā) which, being unmindful, they desire and relish, which is equivalent to craving (taṇhā). This then gives rise to “grasping” (upādāna) and the rest of dependent origination follows as normal.

(In MN 38 “grasping” is the point at which the “normal” dependent origination takes over. It may be just a coincidence, but in DN 15, too, the sequence is also presented in an unusual way until grasping. I’m not sure if this is significant.)

What is significant, however, is the way the definition of grasping changes. Let’s see an overview of the factors leading up to grasping from SN 12.2:

- And what are the six sense fields? The sense fields of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind.

- And what is contact? … Contact through the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind.

- And what is feeling? … Feeling born of contact through the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind.

- And what is craving? … Craving for sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, and thoughts.

- And what is grasping? … Grasping at sensual pleasures, views, precepts and observances, and theories of a self.

One of these things is not like the other ones! from the time of birth, the factors are all expressed in terms of the six senses. This corresponds to the infant’s growth and gradual capacity to function. Crucially, a child will crave food or comfort or attention. This is a fundamental, even primal instinct, shared in common with animals. It’s very basic.

What is not so basic is having an attachment to views. Kids cry because they don’t get what they want. Adults argue because they have different political opinions. A child has to gradually learn to think, to create concepts, to grasp abstraction, and to form and maintain their own “views” of the world. Adults need this in order to function.

Furthermore, an adult adopts certain rules, moral precepts, religious observances, and the like. They go to church, recite sacred words, or in some way preform actions that align their lives with their own sense of a higher meaning. Even atheists find their own way to do something similar. A child has not yet developed a “world view” and cannot meaningfully do these things. Their parents might take them to the temple, but they have no inner grasp of the meaning of what is going on.

An adult, in addition, develops some kind of theory of self. Note that this is not what the animal psychologists mean when they debate whether a parrot has a theory of mind. This is a much more basic intuitive sense of self-awareness, which in Buddhism would be attasaññā, a “perception of self”. An animal or a small child can have an idea of themselves, they can recognize themselves in a mirror, and perform acts that show they have a coherent sense of themselves lasting through time and even being responsible for actions. But they can’t debate with each other on the merits of behaviorist or functionalist theories of self, or appreciate the different ways the “self” is used in Buddhism and in Jungian therapy. They don’t form articulated conceptions of the self. Adults do, and we can reflect on and discuss these things.

So the step from “craving” (taṇhā) to “grasping” (upādāna) is more than a mere intensification and diversification of craving. It is what happens to craving when it grows up. An adult continues and refines their desire for sensual stimulation. In some ways, their need for gratification is curbed and moderated—we no longer cry when we’re hungry—in other ways it is intensified or even corrupted by cruelty and immoderation. This is implied by the idea of “grasping at sensual pleasures”, no longer merely reacting to basic instincts, but building a life around gratification.

Sensual gratification, however, becomes increasingly bound up with ideas and a sense of self identity. A baby just knows whether they like a food or not; an adult is snobby because they like “better” things than someone else. This conceptual shaping of the world is necessary because an adult is making adult choices: choices to buy this brand of cereal or that; choices of voting for a political candidate who promises us a tax break, or one who promises to treat the vulnerable with decency.

Views and theories shape the way we see the world and the way we act in it. We have to have views; our minds don’t work without them. In spiritual circles it’s common to hear people saying that we shouldn’t have views. Of course that would be a view! What the “no-view” people are really saying is: bow to my views.

Since views affect almost everything we do, we should be careful about the views we have. Views are sticky; they are long-term, abstract structures in the mind. Thoughts come and go, intentions rise and pass, but views, once established, change with glacial slowness.

It is because it this persistent quality of views that they shape, not just this act or that, not just this choice or another, but the whole range of choices that we make through our lives. They direct our kammic choices in a certain flow, like a river directing countless drops of water.

And this persistence and shape of views is what creates the form of our next life, our bhava, the rebirth into a new state. Rebirth is typically not formed by some random act disconnected with one’s character, views, and way of life; it is the outcome of the acts that define your life and who you are.

In Buddhism, as in the law, it is normally understood that full moral responsibility is the domain of adulthood. We don’t treat children or animals as morally responsible agents in the same way. We treat children so that they can learn how to behave, while we treat adults under the assumption that they should have learned. Obviously it is not a black and white area. Children gradually learn a sense of moral responsibility, and within the animal realm, especially with the more intelligent animals, there is a clear sense of morality, of shame or kindness. But full moral responsibility takes an awareness of why one acts and what the consequences are. So while we may hold children or animals accountable for being naughty, we don’t treat them the same way we would an adult.

And in dependent origination, the full cycle is not regenerated until the individual is mature enough to hold views and shape their actions accordingly. We have already seen that the process is not always complete even after birth, as a baby or young infant might die before being able to act as an agent. As a child grows up, they gradually learn to be responsible agents, and the moral and kammic weight of their actions grows accordingly.

This explains why the full weight of kamma takes effect in the human realm. It’s not that animals can’t do good or bad deeds, but generally speaking they are not responsible moral agents in the same way as an adult human.

It takes time and effort to learn how to be a moral agent. If that process is incomplete, the effects of choices in this life will be weak, and the effects of choices in past lives will usually predominate. From the perspective of samsara as a whole, the tragedy of a young death is not just the loss of a life, but the loss of a rare and precious opportunity to learn and grow to create good kamma, and to understand what life is and what it means. Once departed, who knows when that chance will come by again.

We are those creatures, those babies, those little animals, and we have been fortunate enough to make it this far. We get to choose how our view of the world is shaped, and to make our own choices that will shape our lives in the future, or take us beyond this altogether.

Full of interesting points to reflect, in a space without enough explanations inside the teachings neither the world.

Full of interesting points to reflect, in a space without enough explanations inside the teachings neither the world.