Thanks for posting this article and opening this discussion. Tis is indeed [quote=“sujato, post:2, topic:5924”]

an important article.

[/quote]

I have been practising in the Tibetan tradition myself for many years and met quite a few Lamas, and have been given many initiations or “empowerments” in this tradition.

In that little centre where I first met Buddhism, and which became my Buddhist “home” then, the atmosphere was always dominated by a sense of metta and compassion, and also by a critical way of using one’s own mind. This was very good for me, because I was quite naive at the time.

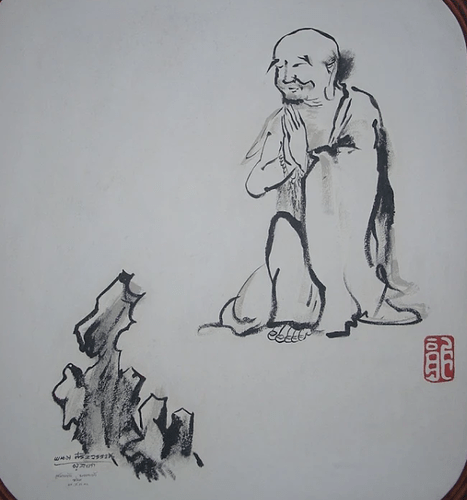

And of course there was often mention of this special kind of relationship between teacher and student, as shown for example in the relationship between Milarepa, the famous Tibetan yogi, and his master Marpa. Marpa made Milarepa perform much hard work and refused to give him teachings until he was physically exhausted and close to suicide. This happened in order to “purify” the bad kamma Milarepa had made earlier in his life - he had killed many people. Milarepa never lost faith in Marpa, his teacher, during this difficult time. And then, when Marpa thought he was ready, he gave him the necessary teaching, and Milarepa made quick progress… That’s how the story goes.

Milarepa plays an important role in the transmission lineage I was involved in, and I always found his story very inspiring. And there wasn’t anything in the behaviour of those teachers I met, especially the ones from the older generation which now has died out, that would make me suspect of things as described in the above article. And I’ve never been offered anything that would involve sexual practices.

At some point I came across articles and books that described various types of abuse happening within the Tibetan community, including sexual abuse, which concerned also well-known and well-respected Lamas, and that was a huge shock to me! On one hand I didn’t want to believe it, but I also didn’t want to base the most worthy thing I was pursuing in my life on a lie! And it never really occurred to me to give up the Dhamma altogether… So I had to find my way somehow through the inconvenient truths.

As years went by I also came across Theravada books and teachings, including the suttas of the Pali canon which the Tibetans unfortunately don’t study at all (or at least the ones I met didn’t). But we started to do that in our little centre, and that broadened my view of Buddhism.

As our centre was always so little it was not attractive for teachers who teach mainly for the sake of making money. (There’s no point of expecting much financial profit when the audience consists of five or six people… ) The Lamas who visited us were mainly coming because of a feeling of connectedness with the first Lama who had been the spark for the foundation of the centre, and who had already passed away when I arrived there. So it was more like meeting with friends, and they would convey us teachings and initiations they would give nowhere else in the West.

This gave me the feeling of being privileged on one hand; but still there always remained that feeling that I would never be fully included. I would never be really told everything, there would always remain something that was hold back. This feeling grew stronger the more I had also contact with people who practised in the Theravada tradition, and this yearning “When will I finally meet ‘my’ guru?” eventually gave rise to the realisation that that even “my” guru would still hold something back!

This was finally the point that made me stop the practices taught by the Tibetan teachers. Together with the fact that with these practices I had never found access into deeper meditation, but with what I learned from teachers like Bhante @sujato or Ajahn Brahm I did - or at least I start to understand how this works, and that it can be done even by me…

What I appreciate so much in the Theravada tradition is the clarity and transparency of the teachings, and it inspires me a lot to see this attitude right at the beginning, in the way the Buddha himself was teaching. And it is such a relief that there is no inherent sense of being included or excluded… The teachings are just there, free and open, for anybody to practice without anything being held back!

One thing is very deplorable in the Tibetan system, and maybe this has something to do with the potential for misogyny and abuse playing an important role there. This is the fact that the Tulkus are taken away from their families already at such a very young age. If I remember right the Dalai Lama was taken to the monastery at the age of four, and others already when only two years old! There they are brought up in a male-only world, abandoned by the woman whom they used to trust before, their mother, not allowed to see her unless once or twice a year or so. Even if this was said to happen for the sake of something “higher” - what does a two-year-old understand by that? No wonder that they don’t develop much respect and trust for women!

And in addition to that they are told from this very early age on that they are something special, other than “ordinary” human beings, more advanced, more pure, more worthy of respect. When you are told this from the age of two on you cannot not believe it! If they are really born with more than average good qualities the damage made by that might be limited; but maybe not all of them are… Therefore it shouldn’t surprise that some of the Lamas seem to have strange character traits and behaviour, that they abuse their position of power and the people surrounding them, and women in particular.

All this doesn’t mean that I don’t have an immense gratitude towards my Dhamma friends who are running this little centre: They were the ones who brought me into contact with the Dhamma, and over so many years shared their understanding with me, shared their lives with me! Whatever difficulties they might be in, I wouldn’t hesitate to do whatever I can to help them out! And to my Tibetan teachers too I feel very grateful. Even if today I see many things in a different light, from their perspective they gave me so much! I still do feel privileged, so lucky to have met the Dhamma in this life, and kind teachers who shared with me so much, and who didn’t abuse me even if this potential is inherently present in the system they represent. And Dhamma friends who still are my friends, even if our paths are a bit different now!

Thank you again, @LucasOliveira, for posting this article that provided the opportunity for me to review this most important part of my life, my journey with the Dhamma, and by doing so becoming even a bit clearer about some aspects of it!