The best test would be to try it…eyes closed, perhaps hands over heart…say “love, love, love” (with feeling/meaning). Then try it with “loving-kindness”, or “goodwill” etc.

I do rather like this for “Samadhi”. Especially in reference to “Samma Samadhi” or even in reference to the type one cultivates in the gradual lead up to the Samma variety.

“Jhana” = “meditative state” … how about “deeply unburdened meditative state” or “deeply pleasant, unburdened meditative state”? I realise it’s lots f words for one…but if there was one/few English words to convey what “Jhana” means…this would be a whole lot easier!

Apologies if I am repeating something…haven’t fully read the whole thread.

First time I’ve commented here,  as the topic is close to my field, if not my heart, as I do lots of translation of dhamma articles.

as the topic is close to my field, if not my heart, as I do lots of translation of dhamma articles.

As a speaker of the Thai language, with over 50% of the words borrowed from Pali and Sansakrit, when the original text uses Pali, it’s easy for me to understand and translate. However, Thai people’s interpretation of the Pali words may be corrupted as time has passed since our education system is on the decline. My thought is that when I translate, I will use either Pali or clear Thai meaning in the main text with the other language in parentheses. It looks clumsy, but I think it’s a way to help readers’ understanding of the text as close as possible should they read it in the original text.

I would greatly appreciate your and Ajahn Brahmali’s comments.

With deepest respect,

Dheerayupa

P.S. Even my name comes from Pali!

Hi @Dheerayupa, nice to see you here. For those who don’t know, Dheerayupa is a student of Ajahn Brahm and a professional translator.

Sure, a list of dictionary words in Thai probably shows that over 50% are from Pali/Sanskrit. But Thai itself is from a completely different language family, no more related to Pali than Chinese is to English. English and Pali/Sanskrit are Indo-European languages, while Thai is Tai–Kadai.

And the words that people actually use in Thai are, if I’m not mistaken, much more likely to be native Thai. Pali/Sanskrit words are predominantly (not completely!) technical, like Latin/Greek words in modern English.

If you analyzed the amount of Latin terms in “English”, including all the technical terms in biology, medicine, law, and so on, there’d be a lot, but most of them are not used outside of specialist circles.

In many ways, I think, the role of Pali/Sanskrit terms in Thai is similar to that of Latin/Greek in English. The difference is, of course, that Latin and Greek are Indo-European languages, and hence from the same language group as English.

Here’s the point of this digression. In writing English it is usually considered good style to favor old-English (Germanic) terms over Latinate terms. As Hemingway said,

“There are older, simpler, and better words, and those are the ones that I use.”

Obviously there are many exceptions to this. But on the whole, a style that favors old-English terms will sound simpler, plainer, more honest and more straightforward.

Comparatively, syntactical constructions dominated by latinate expressions communicate verbosity, pomposity, and the deplorable propensity to denominate a spade as a “manual mineral particulate excavation device”.

I suspect that the same is true of Thai (and other languages that borrow from Pali/Sanskrit, such as Chinese). There are, of course, plenty of Pali/Sanskrit words in Thai that have become completely normal, like thamma.

But what of, say, phra phuu mii phra phaak jao? Would it not be better to say something like, I don’t know, luang por? Or, rather than karuṇā, nam jai? These are probably not very good examples, and as you know my Thai is very limited, but I think you get the idea.

Basically I’m saying that it’s a good idea, as translators, to use ordinary, everyday terms whenever we can. That’s what Pali is: the ordinary, everyday language of the times.

It’s not really corruption, just change. Words change meaning, and this happens all the time. Look at the way the word saṅgha has changed since going to the west. It just means that we have to carefully distinguish how words are used in different periods and contexts.

We have exactly the same problem in all Theravada, because most people assume that Pali words mean the same thing in all times and for all people. They don’t. In fact, virtually all the Pali words in common use today have a quite different shade of meaning when found in the context of the early Suttas, which is one reason why I try to avoid using them in translations almost entirely.

But your name, like most Thai surnames, is, I presume, a product of modernity. It was specifically coined in order to co-opt the “prestige” of Sanskrit. I like your Thai name better!

Dear Bhante,

ROFL! ![]()

![]()

You mean my nickname? That is not Thai, either. It is a registered wordmark of Parker Brothers, Inc., first used in 1900 and registered in the United States in 1930. But yes, my name is a product of modernity to give an apparent identity of someone belonging to an educated class.

Most Thai people, except your teacher ![]()

![]() , would kill me if I called the Buddha Lunag Por. But I know what you mean, and I did try using simple language when I translated Ven Analayo’s article ‘Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination’.

, would kill me if I called the Buddha Lunag Por. But I know what you mean, and I did try using simple language when I translated Ven Analayo’s article ‘Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination’.

I will keep in mind the principle you suggested here when one day I have time to translate some suttas for a simple Thai version, not the phra phuu mii phra phaak jao version, which we have right now.

With deepest respect,

Dheerayupa

Well, I did not know that. It sounds Thai to me!

Well, best not then!

For what it’s worth:

muditā - an ‘exulting, unconditional positive regard’ of some sort… solicitous exilience? Hmm…

jhāna - ‘a musing reverie’ of some sort… or maybe ‘trance’ since it doesn’t have to carry connotations of samma-samadhi yet, only connotations of Wanderer states.

samādhi - What about ‘composure’?

saṅkhitta - I like ‘collected’ as well.

bhikkhu - ‘Mendicant’ works; I think even ‘friar’ could work, or else cenobite, but those have Xian flavors. So, mendicant/contemplative/monastic. (‘Oblate’ for white-robed householders, perhaps, and ‘postulant’ for those seeking ordination?)

nibbāna - Extinguish(-ed/-ment)

I came across an interesting translation for mudita. From an exploration of another Indian tradition (Yoga Sutras of Patannjali):

mudita - conviviality

I think this is probably another instance of a word that is well outside of the common vocabulary, but I thought it might be of some interest here. Personally, I still kind of like ‘cheerfulness’ as an ordinary word that conveys an attitude of love encountering joy, along with the mutual/shared connotation of the word.

Here is a link to the relevant passage:

http://www.ashtangayoga.info/source-texts/yoga-sutra-patanjali/chapter-1/item/maitri-karuna-mudito-pekshanam-sukha-duhkha/

…as a footnote, might it be useful to sometimes look at translations for similar concepts occurring in other Indian traditions? Besides the sanskrit yoga sutras of Patannjali I think the 4 Brahma-Viharas also occur in some of the Jain texts which are in a prakrit language as far as I know.

Conviviality is not quite right, it’s more to do with a friendly spirit in a group, rather than muditā. Cheerfulness, maybe!

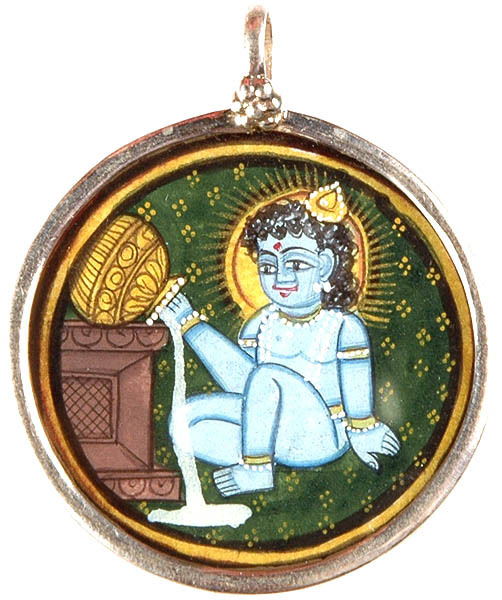

Indeed. Sometimes they definitely have it better. In Vinaya, navanīta is in the Thai forest tradition interpreted as “cheese”, hence is allowable for monastics to eat in the afternoon. But in the Indic traditions it is always rendered as “butter”, which is clearly the correct translation. Krishna is worshipped as the “butter thief”, or the one “smeared with butter” (navanītalipta) after his adorable exploits as a boy:

First time commenting, Bhante. Some thoughts on “mudita”:

“Rejoicing” strikes me as possibly too indiscriminate. Depending on one’s outlook and temperament, one can rejoice in all sorts of things. But it is my understanding that “mudita” carries within its meaning the idea of rejoicing only in what is good or wholesome. If somebody bombs a village and a vengeful onlooker rejoices in the destruction, that’s not mudita.

Words like “cheer”, “gladness” and “delight” seem to have the same problem. They get the affective tone right, but miss the implication of an appropriate object.

It seems to me that mudita is supposed to be the opposite of either envy or resentment. But as a check of an antonym dictionary shows, contemporary English really lacks a good antonym.

How about:

“Generosity of spirit” - the opposite of a cramped, envious, resentful disposition.

“Charity” - I think the older Latin medieval term “caritas” is probably pretty close in signification to mudita, and that earlier English uses of “charity” reflected that meaning. But unfortunately the contemporary use of “charity” has narrowed to refer to acts of giving.

maybe i’m overstretching here but cheer may have something to do with charity etymologically and even with care

charity (n.)

mid-12c., “benevolence for the poor,” from Old French charité “(Christian) charity, mercy, compassion; alms; charitable foundation” (12c., Old North French carité), from Latin caritatem (nominative caritas) “costliness, esteem, affection” , from carus “dear, valued,” from Proto-Indo European *karo-, from root *ka- “to like, desire”

charity | Etymology of charity by etymonline

although online etymological disctionary isn’t supportive of this suggestion

Thanks for the suggestions! I like charity in the old sense. Perhaps “magnanimity”, but this also has a narrower sense today.

![]()

Dear DKevrick,

But the Buddha always pointed to the direction of what is skillful and wholesome. We should always go to the “heart” and see what we feel. Would you rejoice at the news of someone being beheaded or girls being sold as sex slaves? Of course, the answer would be no. The people who did the actions might have some happiness but for the rest of us, more importantly, to the people effected, it is sorrowful and much suffering.

Even though such events do occur in a daily basis in this world and is a reality, we can still rejoice at the really good, happy, and beneficial things that we experience. No matter how small they maybe, they still count and worth rejoicing. Good enough! The world has enough suffering as it is why not look at the bright side? Just my simplistic thoughts though.

Happy holidays to everyone!

with añjali and mettā,

russ

![]()

Then, for mudita, perhaps “beneficence”?